L'infinito

We're in the middle of eclipse season and approaching Autumnal Equinox, and the political atmosphere of the United States is in turmoil, actually, I'd say the entire joint is in shambles - and for good reason - karma.

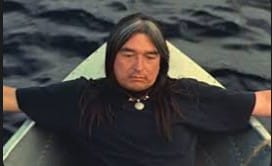

I was compelled to watch Clearcut - witnessing a world from 1991 - a world I remember that no longer exists - and how pathetic that is for me - being white in the United States. The indigenous ancestors remember a land VASTLY different - a vision that brings both immense grief and shame for me, unlike Rickets from the film, as Arthur shows him the grandeur of the land, and he asks, "Do you see?!" and Rickets responds, "No."

Then I had a thought as the film concluded about Arthur as a Wisakedjak, a trickster spirit of water, and the Lady of the Lake of the Arthurian legend. Water is grief’s element. It gathers in the lungs, it burns in the eyes, it swells rivers and carves canyons. Grief lingers in water because water holds memory. It doesn’t just pass by; it absorbs, carries, recalls. Every river is a witness, every lake a ledger. When we cough, when our eyes sting, it is the body remembering what law refuses to record. When Arthur sings in the sweat lodge and the white men cough, they are drowning in the grief they’ve denied. When the Lady of the Lake lifts Excalibur from the depths, perhaps she too is not offering glory but grief — the blade as a reminder that justice cuts only because the land has bled first.

What if the Lady of the Lake, like Arthur, is not a gentle faerie queen but a water-trickster of justice, cruel only because we forget? Her grief is the grief of the land itself, the water remembering what human law will not. Justice is not balance scales in a marble hall; it is water, lungs coughing, rivers carrying memory we cannot dam.

Several sources can tell you that water holds memory. Indigenous knowledge keepers tell us that water ‘bears the memory of the rock that has been in it.’ Contemporary science, too, has debated whether water carries the imprint of what it touches. Whether you listen to ceremony or lab bench, the message is the same: water remembers. What would the water of the Earth and the Cosmos converse about? The joy of creation? The grief of that creation's destruction by humanity? With this notion in mind, who is there to keep the balance? Perhaps it is the tricksters? Tricksters come when we try to control justice. The Ojibwe call him Wisakedjak. The Celts called her the Lady of the Lake. Ed Justin's poem gave us Pumpkinhead. None of them obeys human morality. They rise from earth and water to show us what we refuse to see.

Peter MacQuire, the attorney for the Ojibwe Nation in Clearcut, manifests Arthur in both words and ceremony. Peter tells the Council leader, Wilf, that the Plan Manager, Bud Rickets, should be kidnapped and skinned alive for his part in the logging. After this, they enter the sweat lodge, where Peter sees Arthur emerge from the waters in a vision. The next day, Arthur appears. Peter, Arthur, and Wilf go into town on a small motorboat. The dock they leave from, a single lantern hangs from a post, like the dock one would envision the Ferryman of the River Styx to be stationed at to ferry souls to and fro. Peter has no idea what his request for revenge on behalf of the Ojibwe and the land actually meant - he's still deeply embedded within the colonial system. Arthur will reveal that divine justice is well outside human thoughts and most certainly its laws. As Bob Marley once said, "You will never find justice in a world where criminals make the laws." Arthur reveals this truth to Peter in horrifying ways throughout the film.

Through all the film’s imagery, the one that seared deepest for me was the boat scene, when Arthur and Peter speak about oral traditions. Peter brags that he has read many books on the Cree and Ojibwe, and Arthur laughs — because book-learning is paper without breath. Then Arthur reaches into his sack, pulls out a green serpent, bites its head off, spits it aside, and declares: “That’s oral tradition!”

The serpent — ancient emblem of wisdom, transformation, and continuity — becomes something else in Arthur’s mouth. By biting off its head, Arthur reminds us that wisdom is not stored in archives, not even in the serpent’s coil of memory. Wisdom is alive only in the tongue, in the act of telling. Oral tradition is violent against forgetfulness. It shocks, it scars, it demands witness. The magic is not in the book but in the bite — not in the serpent’s body but in the teller’s tongue.

If Arthur biting the serpent shows us that wisdom lives in the tongue, then the Lady of the Lake lifting Excalibur shows us that justice lives in the hand. Both acts are violent, both are shocking, both come from the waters. The serpent’s wisdom is severed and reborn through story; the sword’s power is submerged and returned only when the land demands it. These are not polite gifts. They are reminders that true wisdom and true justice are never gentle.

Arthur spits out the serpent’s head as if to say: “Forget your books — remember through blood and voice.” The Lady of the Lake rises with Excalibur as if to say: “Forget your crowns — remember through the land’s grief.” One strikes with teeth, the other with blade, but both are water-tricksters revealing the same law: human systems forget, water remembers.

At the end of the film, Arthur slips back beneath the waves, claimed by the same waters that birthed him. When the men return, Peter sees Polly, a young girl now wearing Arthur’s pendant — an eight-pointed star, a sacred Cree symbol of cosmic origin, the four directions, the four stages of life, and Star Woman herself. The trickster has not vanished; he has been carried forward. Oral tradition is not just stories told — it is symbols passed, burdens inherited, memory carried in new bodies.

Earlier in the film, when Peter presses Arthur about his tribe, Cree or Ojibwe, Arthur claims neither. Arthur laughs and turns the question into a teaching, reminding us that oral tradition resists confinement. Perhaps Arthur belongs to both, and yet to neither — like water itself, flowing between boundaries, belonging everywhere and nowhere. That is the paradox of the trickster: he refuses the categories of empire, just as water refuses the shape of any vessel. He is grief and justice, serpent and song, sword and star

And so Arthur sinks, and Polly rises with the star, and the river keeps its course. I think of Leopardi’s words — l’infinito — the infinite, not as vast sky, but as grief’s depth and water’s memory. That is where the trickster lives, where justice breathes, where I have learned to see.

I leave you with Leopardi's L'Infinito

Sempre caro mi fu quest’ermo colle,

e questa siepe, che da tanta parte

dell’ultimo orizzonte il guardo esclude.

Ma sedendo e mirando, interminati

spazi di là da quella, e sovrumani

silenzi, e profondissima quïete

io nel pensier mi fingo; ove per poco

il cor non si spaura. E come il vento

odo stormir tra queste piante, io quello

infinito silenzio a questa voce

vo comparando: e mi sovvien l’eterno,

e le morte stagioni, e la presente

e viva, e 'l suon di lei. Così tra questa

immensità s’annega il pensier mio:

e 'l naufragar m’è dolce in questo mare.